By Christos Richards, Partner, Calibre One

Studies of gender and ethnic diversity consistently demonstrate that diversity in leadership enhances the overall effectiveness of boards by fostering a range of viewpoints that offer value. Diversification in the boardroom improves the quality of board performance, encourages objectivity, and expands the quality of debate and decision making. Adding board talent brings new perspectives, skills, and experiences; tapping diverse talent can foster innovation, creativity, and expand problem-solving approaches, offering vital new perspectives and ideas.

The progress of women in leadership and business — and deserved recognition for their contributions — has been a hard-fought journey for many decades. To acknowledge and reward the value that our female colleagues deserve is an imperative which extends beyond representation, beyond driving social change, and beyond fostering inclusive growth. However, much more work needs to be done at the top with the composition of corporate boards.

For decades, I have been an advocate for diversity and, particularly, the appointment of women as independent directors. Published in Life Science Leader in April 2017, my article (Diversity In The Biopharma Boardroom) proved timely as optics continued to open up on best practices in corporate governance and behaviors in the boardroom. The makeup of corporate boards had begun a period of transformation.

The change was needed, and the recognition that diverse boards tend to outperform gained momentum. One result was legislature in California in 2018 with the passing of SB 826. The bill required public corporations with principal executive offices located in California to include a specific number of female board directors, depending on overall board size. By December 31, 2019, all public corporations located in California would be required to have at least one female director on their board. By 2021, public companies were to be required to have at least two female directors if the board had five directors, and three female directors if the board had six or more directors. Financial penalties would apply for corporations failing to meet these requirements. Beyond those fines, influential institutions would also vote with their investments.

In 2020, California continued to play a leadership role passing AB 979, requiring that publicly traded companies located in California, no matter where incorporated, would also be required to add a minimum of one director from an “underrepresented community.” AB 979 defined a director from an underrepresented community at that time as a director who self-identifies as Black, African American, Hispanic, Latino, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, Native Hawaiian, or Alaska Native.

Disappointingly, certain groups attempted to negate this hard-won and overdue progress with challenges to California’s board legislation championing diversity. These included California lawsuits filed in two cases, Crest v. Padilla I and II in 2019 and 2021. Fortunately, NASDAQ followed with applaudable leadership and adopted its own standards requiring companies listed on the exchange to have women and minority directors on their boards. Companies not in compliance would have to explain why. Though NASDAQ also was challenged legally, the SEC approved this standard, which if it ultimately stands, will require companies to appoint two diverse directors by 2026.

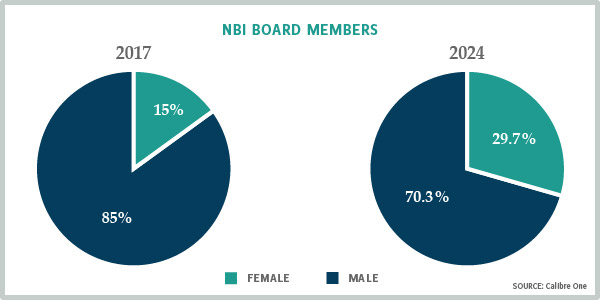

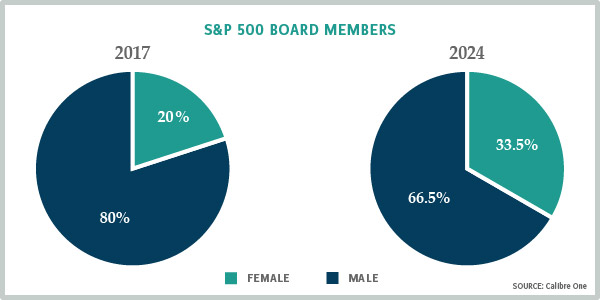

Throughout these past seven years since 2017, the biopharmaceuticals sector has made material strides. In 2017, I reported on board composition of the NASDAQ Biotechnology Index (NBI). In the first quarter of that year, the publicly traded companies in the NBI reflected just how much work needed to be done, with only 15% of the board members of those 167 companies having appointed female directors (See Figure 1). Astonishingly, 26% of the companies in the index at that time were still without a female director. In comparison, among S&P 500 companies, women held 20% of board seats in 2017 (See Figure 2) and only two percent of those boards remained all-male. Big Pharma companies were ahead of biotech’s curve: among the traditional Big Pharma companies, 26% of board seats were held by women and every Big Pharma board had at least one female director in 2017.

Figure 1: NBI Board Member Gender Diversity 2017 and 2024

Figure 2: S&P 500 Board Member Gender Diversity 2017 and 2024

Over the past seven years, the NASDAQ Biotechnology Index has expanded, and was represented by 221 companies on March 1, 2024. Those 221 companies globally (184 headquartered in the U.S.) share a total of 1,894 directors. Encouraging is that 29.7% of these board members are now women (Figure 1) and remarkably only one company in the NBI is now without any female representation on the board. Domestic statistics are equally encouraging with 469 women representing the 1,555 U.S. directors in the NBI (30.16%).

For a corporate board to enhance company performance, ensuring gender-diverse leadership teams must be a priority. A diverse board offers a wealth of perspectives that spur innovation, improve decision making and boost employee engagement. Inclusive leadership in governance impacts and extends beyond the boardroom, and beyond the individual company. Entire industries are experiencing transformation, and fostering and supporting diversity in the boardroom has become pivotal, not only in the field of healthcare, but in every global industry sector. This mission is vital if we are to address the daily challenges and risks faced while striving to ensure an equitable and sustainable future.

In parallel, the balance of directors in the boardroom often offers a window into a company’s culture. Just as the experienced CEO will look at the composition of a board and evaluate its independence, other C-Suite leaders are examining the makeup of your board of directors, with an eye on diversity. The savvy CEO has begun to shy away from a startup where the board is largely investor based and lacking in independence. Mindful that the board may be a proxy to how a company operates, women in leadership have grown increasingly wary of opportunities in environments where there is clear gender disparity.

Moving Beyond Good Intentions And The Biopharma C-Suite

To access boardroom talent in a highly competitive market, it is valuable to understand how the board search process has been managed for years, and how that is changing. From the formation of the first corporate board, directors historically mined their own networks for talent. Not surprisingly, a male dominated board gravitated to candidates with the same gender or racial profile. As a result, it would take decades for a woman to be appointed to a corporate board. A survey of Fortune 250 companies in 2012 found that the first female director of those surveyed companies was Clara Abbott as a director of Abbott Laboratories in 1900.

These common practices permeated corporate behavior for decades, but began to shift more acutely in 2002, the year of the Enron scandal. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (“Sarbanes”) brought increased pressure on corporate behavior, particularly with respect to principles of corporate governance, and the manner in which legal and accounting firms interact with their clients. Scrutiny triggered increased accountability, and board independence took center stage as governance teams deliberately set about changing boardroom behavior. But change did not come easily, and certainly not fast enough. Independent directors were the focus, with little attention to diversity.

Finally, after more than a decade ignoring the gender disparity on boards, regulators and investors began to take notice and stepped-up pressure on companies to correct these inequities. Nominating committees responded, starting out eager to add a woman to their board’s roster. But they found themselves falling back on default behaviors, with traditional recruiting patterns directly impacting intended processes. These were compounded by a range of barriers, from stereotyping about aptitude and capabilities, to unconscious bias.

There were also expectations instilled by decades of practice that stood in the way. Nominating and governance committees, though committed to change, had for years prioritized previous board experience as an almost ‘must have’, with title and prominence of position equally weighted. If an experienced director, or a sitting or recently retired CEO was the desired profile, the consequence was clear to see. The lack of female and racially diverse CEOs overwhelmingly narrowed the talent pool, and even responsible and committed recruiting partners were pressured to focus on the name brand director candidate.

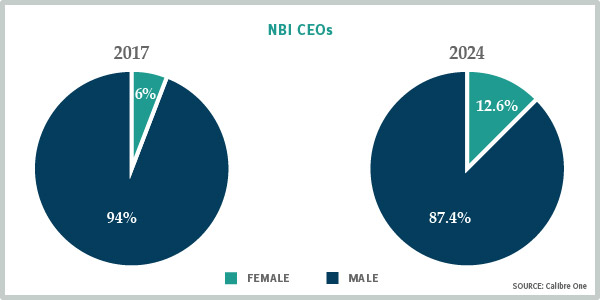

Fortunately, the change in the boardroom, though more gradual than ideal, also began to influence the composition of the corporate C-Suite. In 2017 there were a mere nine sitting female CEOs in the NASDAQ Biotechnology Index. Those nine were either at maximum board capacity, and/or serving companies whose boards restricted the number of outside board commitments they were allowed. Today, the NBI reports 28 female CEOs, with 25 of those in the U.S. (See Figure 3). But these numbers still speak to the work left to do with only 12.6% of the CEOs in the NBI represented by women (versus roughly 5.5% reported in 2017).

Figure 3: NBI CEO Gender Diversity 2017 and 2024

These CEOs alone can’t move the needle. They must manage their own restrictions, amplified in the past seven years by guidance and pressure from the investor community that the public company CEO is now limited to one outside public board. This is a reduction from previous soft guidance that limited board bandwidth to two outside public company boards back in 2017.

Expanding The Director Candidate Pool And Opening The Aperture

Thus, the challenge is to find ways to meet industry’s commitment to change. Boards must strive for the boardroom behaviors and balanced board compositions that embody best practices. Even where legislation fails or bends to bias, leadership must lead, and a commitment to appointing new directors from outside the historically conventional pool of talent is essential.

Building a world class board often requires a series of disciplined strategies, with planned appointments over a period of time designed to rebalance and strengthen. Directors, in addition to being diverse, should also complement each other in skillset and discipline.

Together with my colleagues at Calibre One, we have worked with clients to think through the recruitment process and to open the aperture by employing thoughtful and effective strategies. If a board is committed to change, we are able to assist, and we have never failed in a single board search (across more than 200 board appointments) where the client was committed to appointing a diverse director. These strategies have included, but are not limited to:

- Adding Disciplinary Depth: In the business of BioPharma board building, clients need to identify disciplinary gaps on the board in parallel. The most common tend to be 1) the company builder; 2) the finance expert to either ‘chair’ or strengthen the audit committee; 3) The CSO or CMO leader to either add credibility at the scientific level or broaden the company’s clinical bench strength; and 4) the commercial executive with experience launching healthcare products, often sought as companies launch their first product or expand their commercial agenda.

- Adding Therapeutic or Scientific Specificity: Clients find value in adding technical, scientific and/or medical depth. Value-add with these appointments is most accomplished by deepening the company’s scientific or medical acumen, which for a platform company may be adding experience with technologies in, for example, RNA manufacturing, lipid nanoparticle delivery, or with AI/ML/DL techniques. It may also come with the need to add therapeutic depth which can range across rare or prevalent indication diseases including but not limited to CNS, virology, immunology, or endocrine disorders. In the field of oncology, it may become even more specific with solid or hematological specificity, and even extend to direct specialization with cell and gene therapies, or distinguishing between small molecule or biologic therapeutics.

- Considering The First-Time Director: Many clients have employed the strategy of considering the first-time director. We start by considering those with some experience in governance, which can be gained from service on a nonprofit board. Private company board experience can be a precursor to public company experience, with public company experience for years the ideal. But ISS and Glass-Lewis restrictions created a talent vacuum, and the experienced board director was quickly boarded to maximum capacity. Opening the aperture to consider the first-time director expands the talent pool dramatically. While the Big Pharma executive will often have employer-imposed restrictions, biotech has proven more flexible, and fortunately in biotechnology, service in the C-Suite has exposed talent to boardroom dynamics. It is quite common that a CMO, CCO, CBO, or CFO presents regularly to their board. Further, their participation and contributions to raising capital, investor interactions, and business development and alliance management has offered experience that translates into the boardroom.

- Industry Cross Pollination: Cross pollinating from other sectors has long been an accepted strategy for strengthening a board while expanding the talent pool. As just one example, the pace of high tech can mirror that found in a biotech or life sciences company. Companies who need to commercialize find that adding experience from the payor and reimbursement community can offer significant value. For those with pipelines of products which may be both reimbursed or self- paid by the customer, leaders with DTC experience can provide greater insights into how to reach and influence the customer. We also have found unique experience brought by financial, human resource, and legal talent from other sectors where cross pollination can offer unique insights and learnings gained in other industries. I cited examples of this strategy in 2017 with payer and reimbursement experience for one rare disease client, and a luxury goods CEO for an aesthetics company. Others have included the addition of a high-tech CEO who had previously been at Proctor & Gamble strengthening an aging/longevity company’s board. In another case, adding a high-tech CFO with experience honed at HP to the board of a proteomics company was well received. Each of these strategies accessed talent that would not have been considered by most search firms and their clients, adding talent that had helped build billions in value.

- Thinking outside of the box (STEM): The intersection of technology with the life sciences and biopharma sector has continued to accelerate over the past decade, revolutionizing the field of healthcare and the development of therapeutics, diagnostics, and medical devices. At the tip of that spear sits science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), all driving innovation while transforming the fields of healthcare and medicine. Technology has helped us accelerate drug discovery, manage clinical information and data, and develop drug delivery methods, systems, and devices, all designed to deliver and speed the pathway for approved products and solutions that will optimize patient treatment. The fields of technology, engineering, computer science, and math open up a new horizon of leadership that has the potential to contribute to our sector in the boardroom. Importantly, competitive concerns can be alleviated by mining other sectors for boardroom talent.

Keep Marching Down The Road To Diversification

Women are reshaping our future, remodeling leadership, and their contributions are profound, transformational, and inspirational. Women found their voice decades ago, and it took time for society and industry to learn how to listen. Let’s remain committed to learning and to listening. If we do, our sector, healthcare as a whole, and most importantly, the patients we serve, will all benefit.

About The Author:

Christos Richards is a Partner at Calibre One, based in Los Angeles. With 30 years of global executive search experience, including 25 years focused on serving biopharmaceutical and healthcare clients across North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia, Christos has completed more than 350 Executive level assignments, including over 200 Board, CEO, and CEO succession projects in the Life Sciences sector. He serves clients ranging from venture-backed startups to leading global enterprises in devices, diagnostics, agricultural biotechnology, animal health, tools, services, and digital health sectors.

This article was originally published in the Life Science Leader